The Drive for Food

The drive for food, or hunger, is primarily a survival mechanism. It ensures that organisms, including humans, acquire the necessary nutrients and energy to sustain bodily functions, grow, and repair tissues. Nutrients and energy are also required for reproduction. More on that later. The drive for food, we’ll call it hunger, is regulated by a complex interplay of hormones, neural circuits, and feedback mechanisms involving various organs and the brain.

- Biological Mechanisms: The hypothalamus plays a central role in regulating hunger and satiety. Hormones such as ghrelin, produced in the stomach, signal hunger to the brain. You can remember ghrelin as the hormone that makes your stomach growl…“G for growl and G for Ghrelin.” Leptin, another signaling hormone produced by adipose (fat) tissue, signals satiety or fullness. The amount of glucose in your blood and other metabolic signals also influence hunger.

- Behavioral Aspects: Hunger drives organisms, including people, to seek and consume food. For many animals, this involves foraging, hunting, or scavenging. In humans, cultural and social factors also influence eating behaviors. The drive for food can lead to competitive behaviors in environments where resources are scarce. Unfortunately, in today’s first world, foraging, hunting, or scavenging in our supermarkets does not require expenditure of many calories, giving way to problems of obesity.

- Evolutionary Significance: Ensuring a steady intake of food is crucial for maintaining energy levels and overall health. Evolution has favored traits and behaviors that enhance an organism’s ability to find and consume food. For example, the development of sensory systems to detect food and the evolution of digestive enzymes to process diverse diets are direct results of this drive.

The Drive for Sex

The drive for sex, or reproductive drive, is essential for the continuation of a species. Unlike the drive for food, which is necessary for individual survival, the reproductive drive, at least in heterosexuals and barring contraception, ensures the passing of genes to future generations. This drive is influenced by hormones, environmental cues, and social interactions.

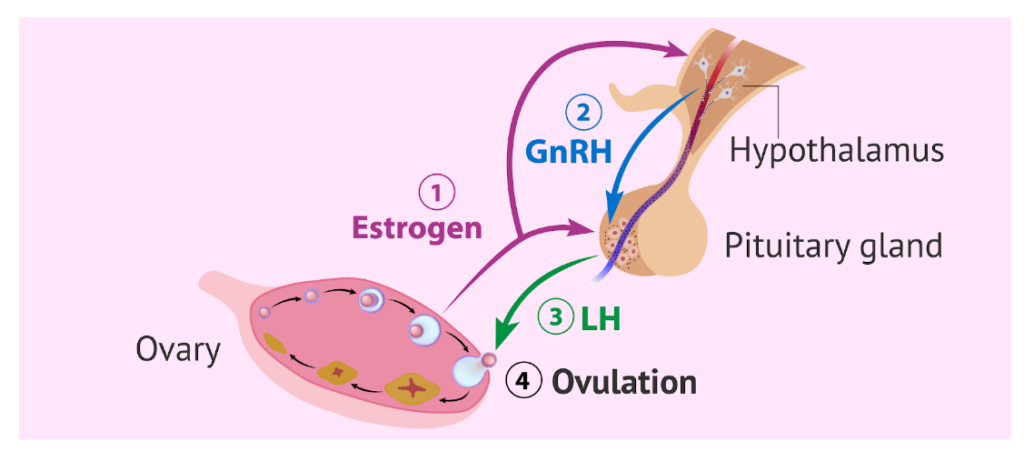

- Biological Mechanisms: Sex hormones such as testosterone and estrogen play crucial roles in regulating sexual behavior and reproductive functions. The hypothalamus releases GnRH (Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone) which stimulates the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland – also located in the brain – is in charge of regulating the production of FSH (ovarian Follicle Stimulating Hormone) and LH (Luteinizing Hormone). FSH grows the ovarian follicle – a small fluid-filled sac in the ovaries – and the egg within it, and LH triggers ovulation, the release of that egg (See Figure 1). Pheromones, chemical substances that are released to elicit behavioral responses in individuals of the opposite sex, and other environmental signals can also trigger sexual behavior. While there’s still no definitive evidence that humans have pheromones, some potential human pheromones include androstadienone, which is found in male sweat, and estratetraenol, found in female urine.

Figure 1.

- Behavioral Aspects: Sexual behaviors are diverse and can involve complex courtship rituals, mating displays, and social interactions in animals, including humans. In many species, sexual selection has led to the evolution of traits that enhance mating success, such as bright plumage in birds or elaborate courtship dances. I guess you can think of social media and dating apps for humans in that way as well.

- Evolutionary Significance: The reproductive drive ensures genetic diversity and the propagation of advantageous traits. Sexual reproduction combines genetic material from two parents, creating offspring with unique genetic combinations. This genetic variation and diversity is crucial for adaptation and evolution.

Differences in Biological Drives (Food vs Sex)

While both drives are fundamental, they differ in several keyways:

- Immediate vs. Long-term Goals: The drive for food addresses immediate survival needs, while the drive for sex focuses on longer-term reproductive success. As it relates to human reproduction, longer-term success typically means 14-18 or more years, or until children can produce and raise the next generation.

- Regulatory Systems: Different hormonal and neural systems regulate these drives (see part one of this blog above: “The Masturbation Diet: The Scientific Underpinnings”). Hunger is primarily managed by metabolic signals and hormones related to energy balance, while sexual behavior is regulated by sex hormones and social cues.

- Behavioral Expression: Hunger leads to behaviors aimed at acquiring and consuming food. In contrast, sexual drives lead to behaviors focused on attracting mates and reproducing.

- Evolutionary Pressures: The drive for food has led to adaptations that improve foraging efficiency and nutrient absorption. The reproductive drive has led to the evolution of traits that enhance mating success and offspring survival.

The interplay between the state of being satiated with food and the desire for sex offers a fascinating glimpse into human physiology and behavior. Both fundamental drives—hunger for food and hunger for sex—are regulated by complex neurobiological systems, and their interaction influences our behavior in significant ways.

Impact of Being Full of Food on Desire for Sex

- Biological Mechanisms: The state of being full, or satiety, primarily signals to the body that it has received sufficient nutrients and energy. This state is regulated by hormones such as leptin and insulin, which signal the hypothalamus to suppress hunger. Interestingly, the hypothalamus also plays a crucial role in regulating sexual behavior. When the body is satiated, the energy that would otherwise be diverted to seeking food can be allocated to other activities, including reproductive behaviors. However, one can have too much of a good thing. For example, my observation of the “No One Has Sex on Thanksgiving” phenomenon may be illustrative of this point. The fullness (turkey, potatoes, stuffing, green beans, apple pie, pumpkin pie, etc.) reduces sexual activity following the holiday meal leading to the lowest sales of “the morning after pill” following Thanksgiving of any of the major holidays. Circumstantial or biological?

- Energy Allocation: The body’s allocation of energy resources is a fundamental aspect of how being full affects the desire for sex. In an evolutionary context, when food is scarce, energy is prioritized for survival rather than reproduction. Conversely, when food is abundant, energy can be redirected towards mating efforts. This shift is crucial for species survival, ensuring that reproductive activities occur during times of plenty when the chances of offspring survival are higher as well.

- Neurotransmitters and Hormones: The regulation of hunger for food, and sexual desire involves overlapping neurotransmitters and hormones. Dopamine, for instance, is involved in the reward systems of both food intake and sexual activity, especially with associated orgasm. After eating, dopamine levels rise, contributing to feelings of pleasure and satisfaction. This increase in dopamine can enhance mood and potentially heighten sexual desire. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter whose levels rise after eating carbohydrates, has a complex role. While it can improve mood, high levels of serotonin are also associated with reduced libido (“No One Has Sex on Thanksgiving” or use of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor type antidepressants [SSRIs]).

Desire for Sex Influenced by Fullness

- Immediate vs. Delayed Gratification: Being full can shift focus from immediate survival needs to longer-term goals, such as reproduction. When immediate needs are satisfied, the body and mind are free to pursue other drives. This shift can manifest in increased attention to social interactions and mating opportunities. In essence, fullness or satiation frees cognitive and physical resources, allowing individuals to engage in sexual behaviors.

- Psychological Factors: Psychological well-being significantly influences both hunger for food and sexual desire. Feelings of fullness and satisfaction can enhance overall mood and reduce stress, which in turn can increase sexual desire. Stress and anxiety often dampen sexual desire, so the relaxed state following a good meal can create a conducive environment for intimacy.

- Cultural and Social Influences: The cultural context also shapes how fullness and sexual desire interact. In many societies, food and sex are intertwined in rituals and social practices. Shared meals can lead to bonding and increased intimacy, setting the stage for sexual activity. The act of eating together can serve as a prelude to courtship and mating behaviors.

Shifting the Balance in Challenging Times

So, if you’ve gotten this far, you’re probably thinking “How do I change the balance between my desire for food and my desire for sex,” if I need to lose weight or my libido is lagging or both? While a complete explanation is beyond our time and space here, here’s the ultrashort version.

Weight Loss, Decreased Desire for Food: There are several classes of medications documented to reduce desire for food. The two most commonly used classes today are: 1) stimulants, like those used for attention deficit disorder (ADD), which reduce desire for food, increases cognitive focus, and motivation, while keeping metabolism going (i.e. phentermine [Adipex, Lomaira], phentermine/topiramate ER [Qsymia], etc.), 2) medications that decrease hunger while making one feel full despite their caloric intake being low, known as GLP-1 receptor agonists. First used to treat type 2 diabetes, they have also shown impressive amounts of weight loss. (i.e. liraglutide [Saxenda], semaglutide [Wegrovy], and tirzeptide [Zepbound], and several others in development).

Increased Sexual Desire AND Decreased Desire for Food: There are a few special agents which have a unique place in therapy because they can do both: reduce appetite for food while also increasing desire for sexual activity. If you have been reading carefully, you should be thinking: that’s not possible evolutionarily speaking! How can we simultaneously reduce appetite and increase sexual desire?

Here are three exceptions to our evolutionary rule: bupropion (Wellbutrin), flibanserin (Addyi), bremelanotide (Vyleesi). Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant, FDA approved for that mood disorder. During its development for depression, it was found to increase sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm at higher doses while simultaneously decreasing weight. It was subsequently added to an FDA approved weight loss medication, Contrave (naltrexone with bupropion). Flibanserin is FDA approved for treating low sexual desire in premenopausal women in the US, and pre and postmenopausal women (up to age 60 years) in Canada by Health Canada, the Canadian “FDA”. Flibanserin causes weight loss in both pre and postmenopausal women. Bremelanotide (aka PT-141; Vyleesi) is FDA approved for “on-demand” or “as desired” treatment for low sexual desire in premenopausal women. While not used chronically in clinical practice, a safety study with daily dosing demonstrated it caused weight loss. Therefore, bupropion, flibanserin, and bremelanotide can interfere in the normal physiological balance between desire for food and desire for sex. In each case, these medications can decrease desire for food – resulting in weight loss – while increasing desire for sex – leading to more sex.

Conclusion

The evolutionary drives for food and sex are both vital, but they operate through distinct pathways and serve different functions. Understanding these differences highlights the complexity of biological systems and the ways in which evolution shapes behavior to ensure both survival and reproduction. The interaction between the state of being full of food and the desire for sex is a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Being satiated with food can enhance mood, reduce stress, and free up energy for reproductive activities, but may decrease short-term desire for sex. This shift in focus from immediate survival requirements to long-term reproductive success underscores the adaptive nature of these fundamental drives, what might be called: The Masturbation Diet. Understanding this interplay not only provides insights into human behavior, but also highlights the sophisticated mechanisms through which our bodies balance competing needs for survival and reproduction.

References

- Stricker, E. M., & Zigmond, M. J. (1976). Brain Catecholamines and the Central Regulation of Sodium Appetite. Physiology & Behavior, 17(1), 113-120.

- Pfaff, D. W. (2002). Hormones, Brain and Behavior. Elsevier Science.

- Wade, G. N., Schneider, J. E., & Li, H. Y. (1996). Control of fertility by metabolic cues. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 270(1), E1-E19.

- Cameron, J. L. (1996). Metabolic cues and reproductive function. American Journal of Human Biology, 8(2), 179-184.

- Verhaeghe J, Gheysen R, Enzlin P. Pheromones and their effect on women’s mood and sexuality. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2013;5(3):189-95.

- Gudzune KA, Kushner RF. Medications for Obesity: A Review. JAMA. Published online July 22, 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.10816

- Segraves, Robert Taylor MD, PhD*; Clayton, Anita MD†; Croft, Harry MD‡; Wolf, Abraham PhD*; Warnock, Jill MD§. Bupropion Sustained Release for the Treatment of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Premenopausal Women. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 24(3):p 339-342, June 2004.

- Simon J, Derogatis L, Dennerstein L, Krychman M, Shumel B, Garcia M, Hanes V, and Sand M. Efficacy of Flibanserin as a Potential Treatment for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in North America Postmenopausal Women. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9; 168. June, 2012.

- Katz M, DeRogatis LR, Ackerman R, Hedges P, Lesko L, Garcia M Jr, Sand M; BEGONIA trial investigators. Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results from the BEGONIA trial. J Sex Med. 2013 Jul;10(7):1807-15.

- Simon JA, Kingsberg SA, Shumel B, Hanes V, Garcia M Jr, Sand M. Efficacy and Safety of Flibanserin in Postmenopausal Women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: Results of the SNOWDROP Trial. Menopause. 21 (6); 633-640. June 2014.

- Kornstein SG, Simon JA, Apfel SC, Yuan J, Barbour KA, Kissling R. Effect of Flibanserin Treatment on Body Weight in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women With Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: a Post Hoc Analysis. Journal of Women’s Health. Epub August 17, 2017. DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6230. 26 (11). November 1, 2017.

- Simon JA, Kingsberg SA, Goldstein I, Kim NN, Hakim B, Millheisier L. Weight Loss in Women Taking Flibanserin for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD): Insights Into Potential Mechanisms. Sexual Medicine Reviews. EPub June 10, 2019. 7 (4); 575-586. DOI: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.04.003. October 2019.

- Spana C, Jordan R, Fischkoff S. Effect of bremelanotide on body weight of obese women: Data from two phase 1 randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022 Jun;24(6):1084-1093.

- Goldstein I, Kim NN, Clayton AH, DeRogatis LR, Giraldi A, Parish SJ, Pfaus J, Simon JA, Kingsberg SA, Meston C, Stahl SM, Wallen K, Worsley R. Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) Expert Consensus Panel Review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017 Jan;92(1):114-128.